Athletic superstars — or GOATs — share certain traits, according to a recent study. Knowing what they are may help you raise one, or more importantly, draft one.

When drafting a player, it may be as important to know if they have an older brother than their average yards per play. Likewise, if you want to raise an athletic superstar, you should plan for more than one child.

In a book released earlier this month — The Best: How Elite Athletes are Made — social scientist Mark Williams and sports writer Tim Wigmore teamed up identify and examine factors sports superstars share. The commonalities they found suggest that birth order, birth dates, and birth places matter significantly.

Sibling Rivalry Rules

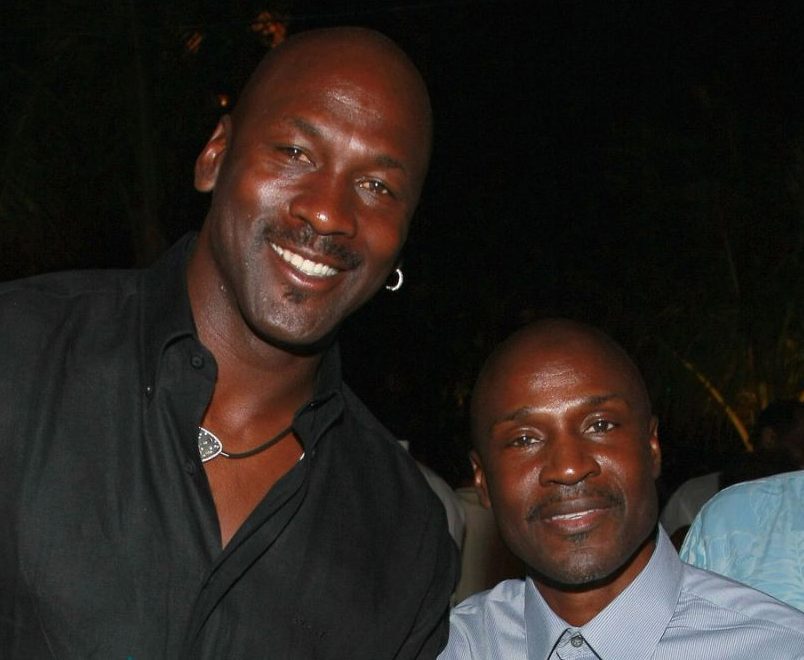

Most notably, the GOAT study found one key is having an older sibling. Michael Jordan, for example, is inarguably one of the greatest basketball players of all time. He credits his brother Larry, 11 months older, for pushing him as a player — a critical relationship that Jordan cited extensively in the ESPN series “The Last Dance,”

Growing up and competing with an older, stronger, sibling has helped a number of superstar athletes.

Serena Williams had Venus to contend with ever since they were children. Andre Agassi, who enjoyed more than 100 weeks in the mid-1990s as the #1 ranked player in the world, started playing tennis with his brother older brother Philip.

And think Peyton Manning was a better quarterback than his kid brother Eli? The eldest Manning child, Cooper, who also played football, might agree.

“Study after study shows that younger siblings have a much greater chance of becoming an elite athlete than older siblings or only children,” Wigmore said in an interview with NPR’s Planet Money.

Luck of the Calendar

But according to data, GOATs don’t benefit from older classmates. Those born in July are usually the youngest in their grade. As a result, they tend to have a harder time both athletically and academically.

The “relative age effect” in sports has been identified by a number of previous studies. For instance, there are 20% more MLB players born in August than in July. Researchers at Freakonomics noted the same effect in European soccer. So, for those born near the school cutoff month, delaying enrollment a year could give an advantage.

However, there is also an observed underdog effect. Williams and Wigmore found that while athletes born late in their school year have a lower chance of turning pro, those who do make it have a higher chance of becoming “super-elites” and winning MVP awards. So when younger kids have to work harder to keep up with the bigger, stronger classmates, it can have similar effect as being pushed around by older siblings.

Location, Location, Location

The study also suggests that location has a lot to do with turning out a GOAT. Rural towns don’t necessarily have the resources to train a world-class athlete. Too often, young talent drops out or gets lost in large cities. Medium-sized cities, with a population between 50,000 and 100,000, seem to be the sweet spot.

Tiger Woods grew up in Cypress, California, which has a population of roughly 50,000. San Mateo, California, Tom Brady’s birthplace, has about 100,000 residents. The Canadian city of Brantford, Wayne Gretzky’s hometown, is also about 100,000 strong.

So if you’re looking to produce the next GOAT, you’ll have a better chance if you move to the suburbs, have a few kids, and don’t conceive them in October.